Package 3

Explore the historical references playwright Jarrett McCreary and designer Sara Outing used in creating the third package in A BREATH FOR US.

To return to the main resource page, click here.

Song of the week: The Temptations, “Ball of Confusion,” 1970

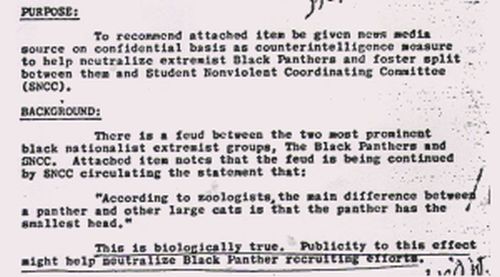

COINTELPRO and FBI Surveillance

COINTELPRO was the FBI’s covert counterintelligence program. It officially ran from 1956 to 1971, though many of its tactics are still in use today. Under FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, COINTELPRO surveilled and worked to disrupt and discredit progressive, communist, and socialist groups, and especially what they termed “Black extremist” groups — those fighting for the liberation and rights of Black Americans. The Black Panthers were a major target of this effort, along with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X.

COINTELPRO’s tactics included wiretaps, blackmail, infiltrating organizations with paid informants and undercover agents, distributing false materials, disrupting social programs, promoting intra- and intergroup tension, and inciting violence meant to falsely paint the organizations as terroristic. They also worked with police departments to arrest, imprison, and even kill members of targeted groups — the Chicago police officers who assassinated Fred Hampton were acting on information provided by COINTELPRO.

COINTELPRO’s efforts succeeded in undermining the Black Panther Party, but groups like the Black Liberation Army (BLA), an underground militant group comprised largely of former Panthers who took more covert and aggressive action, rose in response to the FBI’s tactics.

Learn More:

A brief overview of COINTELPRO

COINTELPRO, then and now

COINTELPRO documents and context, compiled by the People’s Law Office in Chicago

WATCH: Activists discuss their 1971 FBI office break-in, which revealed COINTELPRO’s existence

Tulsa Race Massacre, 1921

After World War 1, Tulsa’s Greenwood District was one of the most affluent Black communities in the United States. It was founded in 1906 when a wealthy Black land-owner, O.W. Gurley, purchased 40 acres of land in North Tulsa and deliberately loaned money and sold land to Black entrepreneurs and settlers to create a space by and for the Black community. In 1921, it was home to thriving businesses and 10,000 residents.

On May 30, 1921, a young Black man named Dick Rowland was accused without evidence of assaulting a white woman in downtown Tulsa. There was a clash at the courthouse between a lynch mob and the Black community members hoping to protect Rowland, and the mob then invaded Greenwood. Over the course of 24 hours, white Tulsans — with the support of the city government — burned 35 blocks of Greenwood, murdered as many as 300 Black residents, and injured hundreds more. Thousands of survivors were left without homes, and the National Guard interned 6,000 Greenwood residents for up to 8 days. No one was ever prosecuted or punished for any of these acts.

In the years after the massacre, Greenwood residents rebuilt the community, without the help and even against the efforts of the city and county government. It continued to thrive until the 1960s.

Learn more:

Tulsa Historical Society and Museum online exhibit, including images, audio interviews, and documents

1921-2021: Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission

The Victory of Greenwood, a series focusing on individual residents and the rebuilding of Greenwood

Elizabeth Catlett's "Homage to My Young Black Sisters"

Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012) was an American sculptor, printmaker, and painter whose work primarily focused on the experience of Black women and issues of social justice. She spent time in Chicago and New York before making her home in Mexico, where she lived, taught, and made art from 1946 until her death. Both Emory Douglas and Barbara Jones-Hogu are among the many artists inspired by her work.

Catlett said, “Art for me must develop from a necessity within my people. It must answer a question, or wake somebody up, or give a shove in the right direction — our liberation.” The sculpture in your package is inspired by Homage to My Young Black Sisters, a 1968 sculpture in red cedar that stands 5.5 feet tall.

Learn More:

Biography and body of work

Elizabeth Catlett and her influence today

WATCH: Dr. Kelli Morgan discusses several Catlett works, including Homage to My Young Black Sisters

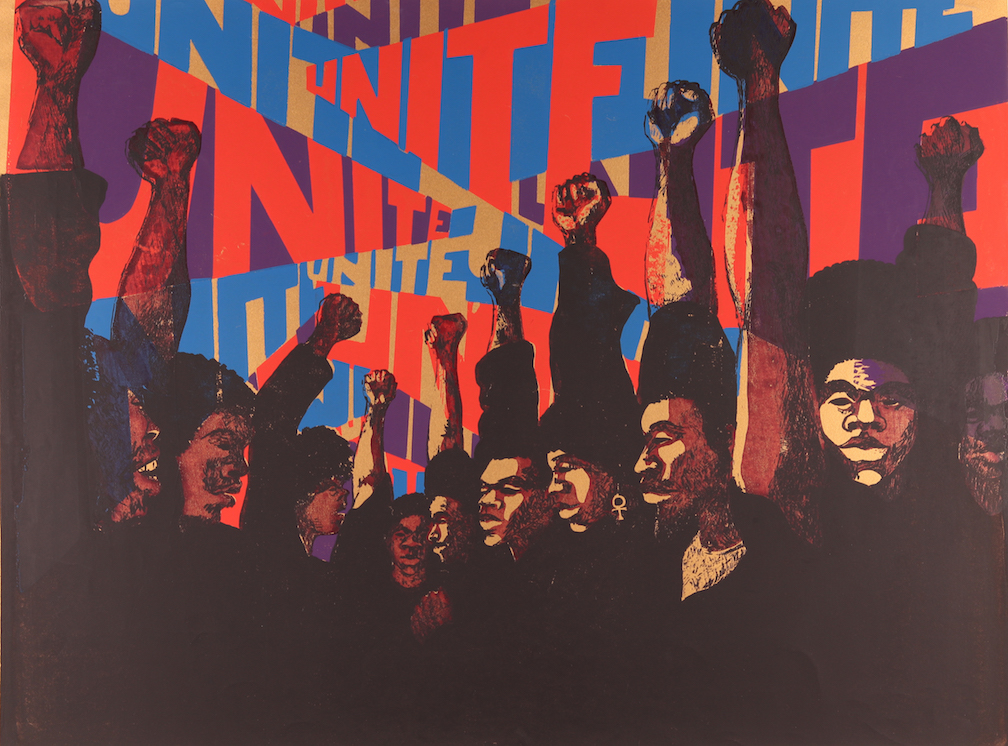

Barbara Jones-Hogu, Artist

Unite is perhaps the best-known work by Barbara Jones-Hogu (1938-2017). It was inspired by Elizabeth Catlett’s Homage to My Young Black Sisters, which Jones-Hogu saw in progress when she visited Catlett’s studio in Mexico. In the world of A BREATH FOR US, Jones-Hogu returns from Mexico with the statue in your package and eventually gives it to her friend Ruthy.

Jones-Hogu was one of the co-founders of AFRICobra (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) alongside Jae Jarrell. Born and raised in Chicago, Jones-Hogu was primarily a painter and printmaker. Her work and AFRICobra’s mission focused on uplifting and affirming Black culture and pride and celebrating the values of self-determination and unity. Jones-Hogu’s art is characterized by strong color and pattern, as well as the incorporation of text.

Learn more:

Brief overview of the artist and this artwork

WATCH: Videos on Barbara Jones-Hogu and AFRICobra from DePaul University’s exhibition guide

Tribute to Barbara Jones-Hogu and her body of work