Package 2

Explore the historical references playwright Jarrett McCreary and designer Sara Outing used in creating the second package in A BREATH FOR US.

To return to the main resource page, click here.

Song of the week: Donny Hathaway, “The Ghetto,” 1969

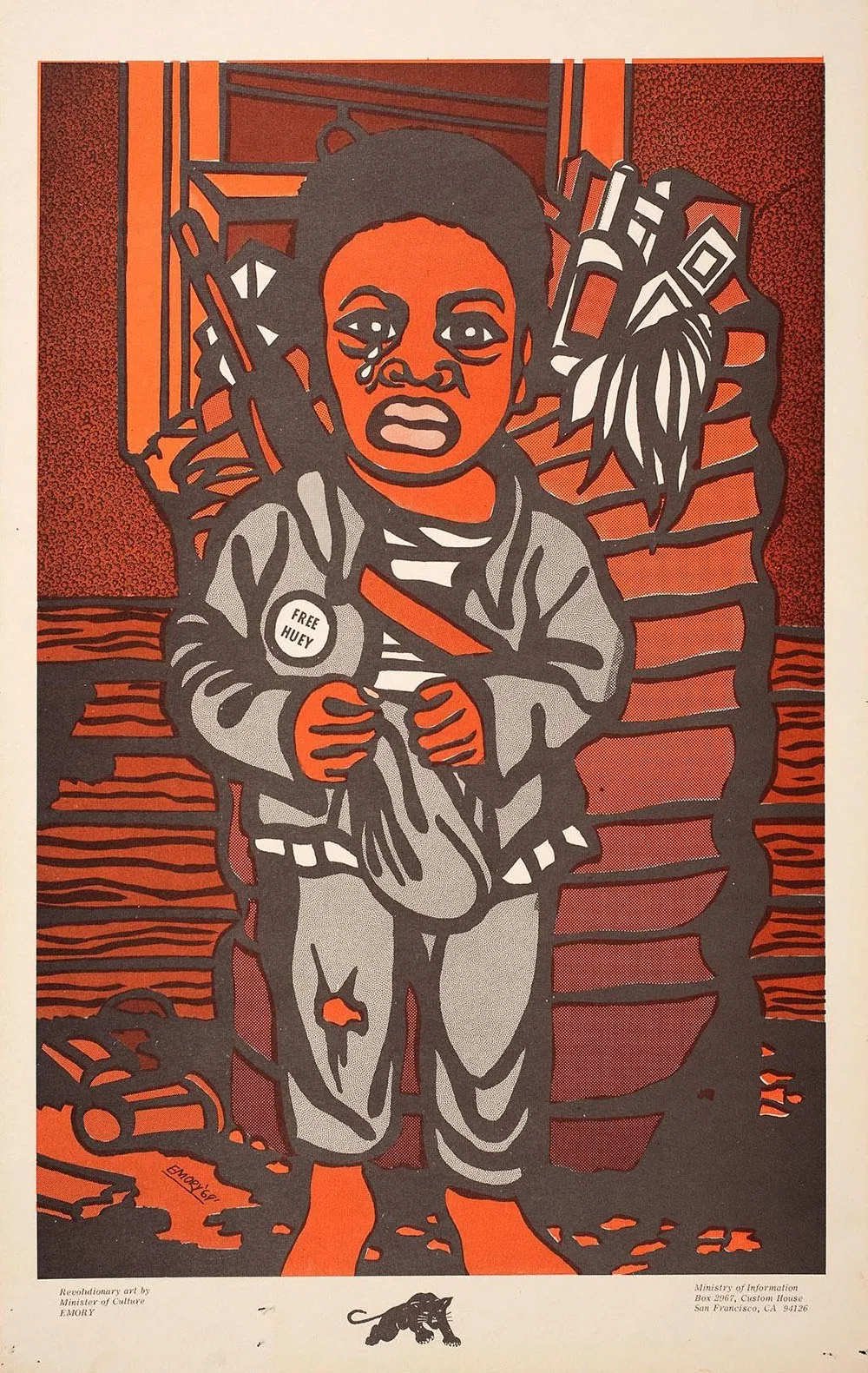

Emory Douglas, Minister of Culture

Emory Douglas (b. 1943) is an American graphic artist. He was the Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party from 1967 until the Party disbanded in 1982, designing and printing their newspaper and other bold graphics such as posters, flyers, and postcards to recruit members and support the Party’s work. The art print in this week’s package is an original design inspired by Douglas’s work, including this print: Free Huey, 1969.

Douglas originally laid out the newspaper using X-Acto knives and glue in Huey Newton’s apartment. At its height, the paper’s circulation was 400,000 a week. Douglas’s graphic art, characterized by bold marker lines and vibrant blocks of color, was intended to create a visual language around social issues and programs and also to help contextualize the articles for those who weren’t able to read the full text.

Today, Douglas is retired, but continues to make art in support of social and political issues.

Learn More:

Emory Douglas’s career and work

Emory Douglas and The Black Panther newspaper

WATCH: Emory Douglas: The Art of the Black Panthers (CW: Includes footage of police brutality)

Movement Print Shops

Revolutionary Suit by Jae Jarrell

Another influence for the original art print in this week’s package is Revolutionary Suit by Jae Jarrell, a clothing, fabric, and furniture designer. The suit is gray tweed, cut in the fashion of 1969, and characterized by a bright yellow bandolier across the chest. The bandolier is filled with colorful wooden dowels – bringing to mind both ammunition and an artist’s kit of pastels.

Jarrell was a founding member of AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists), a group of Chicago artists formed in 1967 and aimed at producing art that affirmed and uplifted the Black community.

Learn more:

LISTEN: Black Fashion History, “Fashion as Wearable Art: Jae Jarrell”

Brief overview of Revolutionary Suit and AfriCOBRA from Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

Interview with Jae Jarrell, MOCA Cleveland

Free Breakfast Program

As part of the Black Panther Party’s pivot to prioritizing social services, Bobby Seale and Ruth Beckford started the Free Breakfast Program in Oakland in January 1969. Churches, local businesses, and community centers donated nutritious food and space, and party members would often get up at 4 a.m. to cook hot breakfasts and serve it to children each morning. By the end of 1969, the program fed more than 20,000 children across 23 chapters, and by 1971 there were programs in at least 36 cities. Alongside the breakfast program, the Black Panthers’ social services of the late 60s and early 70s included medical clinics, food distribution, schools, and an ambulance program, among others.

The FBI identified the free breakfast program as a particular target in their attempts to undermine the Black Panther Party, calling it “potentially the greatest threat to efforts by authorities to destroy what [the Black Panther Party] stands for.” Most programs closed in the early 1970s, but the Seattle program outlasted even the party chapter in the city and operated until 1977. By then, the federal government had dramatically expanded its own free breakfast program – due largely to the success and popularity of the Black Panthers’ program.

Learn More:

Black Panther Party’s Free Breakfast Program

“The Black Panthers: Revolutionaries, Free Breakfast Pioneers”

WATCH: Excerpt from Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution on the Free Breakfast Program

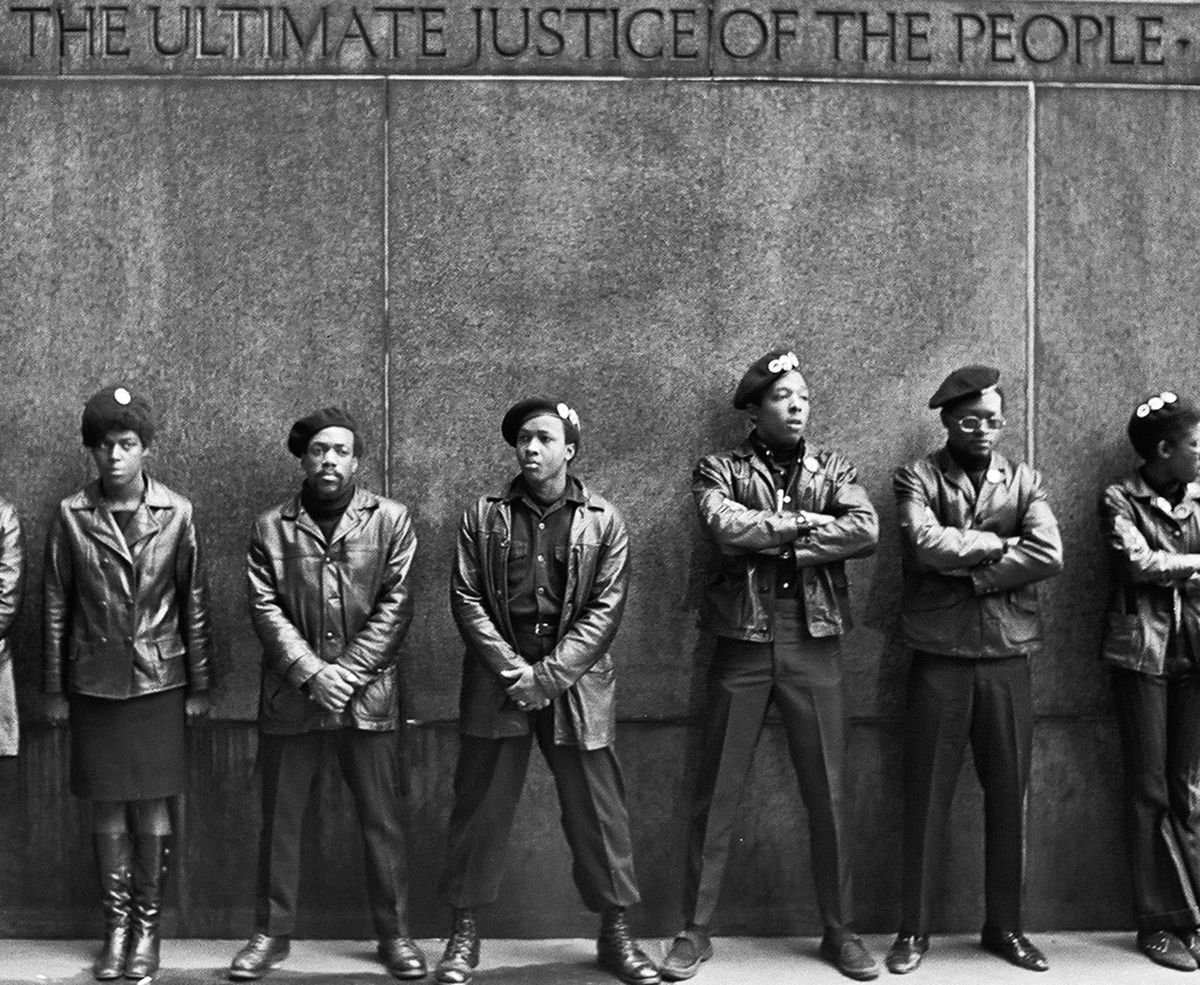

Black Panther Party attire

The most recognizable look of Black Panther party members was the uniform: black leather sports jacket, black pants, blue or black shirt, sunglasses, and black beret. The clothes were chosen for practicality; they were easy to find and utilitarian. The beret was a symbol of solidarity with revolutionaries around the world; according to Huey Newton, “They were used by just about every struggler in the Third World. They’re sort of an international hat for the revolutionary.”

Learn more:

The function and legacy of the Black Panthers’ attire

Black protest fashion, beginning with the Black Panther uniform

The message of the Black Panther’s aesthetic, then and now